The Complex Dance of Curiosity, Awe, and Wonder

Intertwingled

Part 1

“It’s called a true binary.”

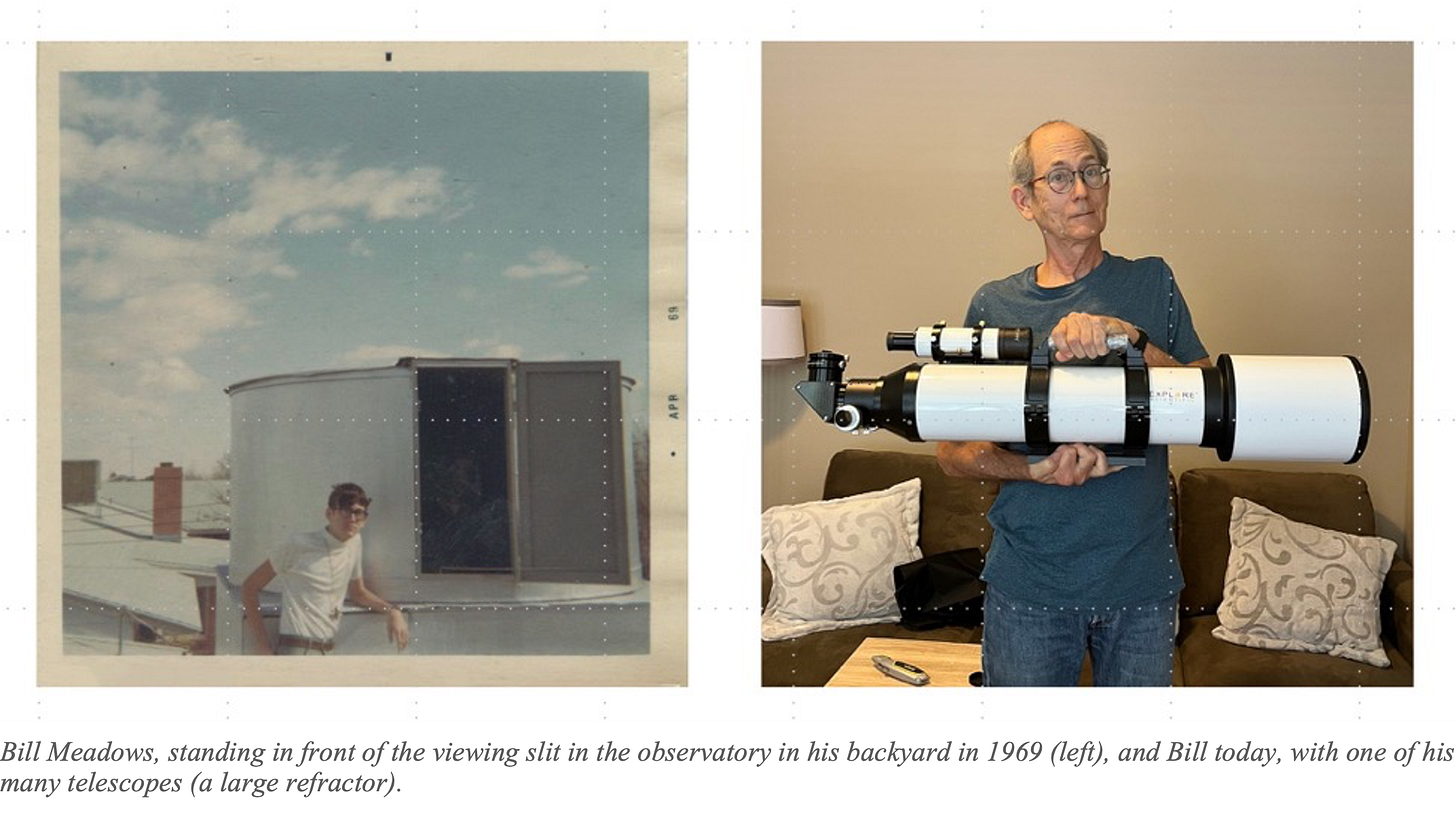

I was 13 years old, and I was standing with my childhood friends Bill Meadows, Peter Norris, and Gil DePaul in the frigid interior of the home-built observatory in Bill’s backyard. The four of us stood in a sloppy circle around the telescope, taking turns looking through the eyepiece and shivering in the late-night winter air.

I like to think that our collective friendship served as the model for the TV show, “Big Bang Theory,” because just like Leonard, Howard, Sheldon, and Raj, our world revolved around the wonder of science and was powered by our collective curiosity. The main difference was that in our cadre, the counterparts for Penny, Amy and Bernadette were conspicuously absent. Clearly, we had not yet been introduced to awe.

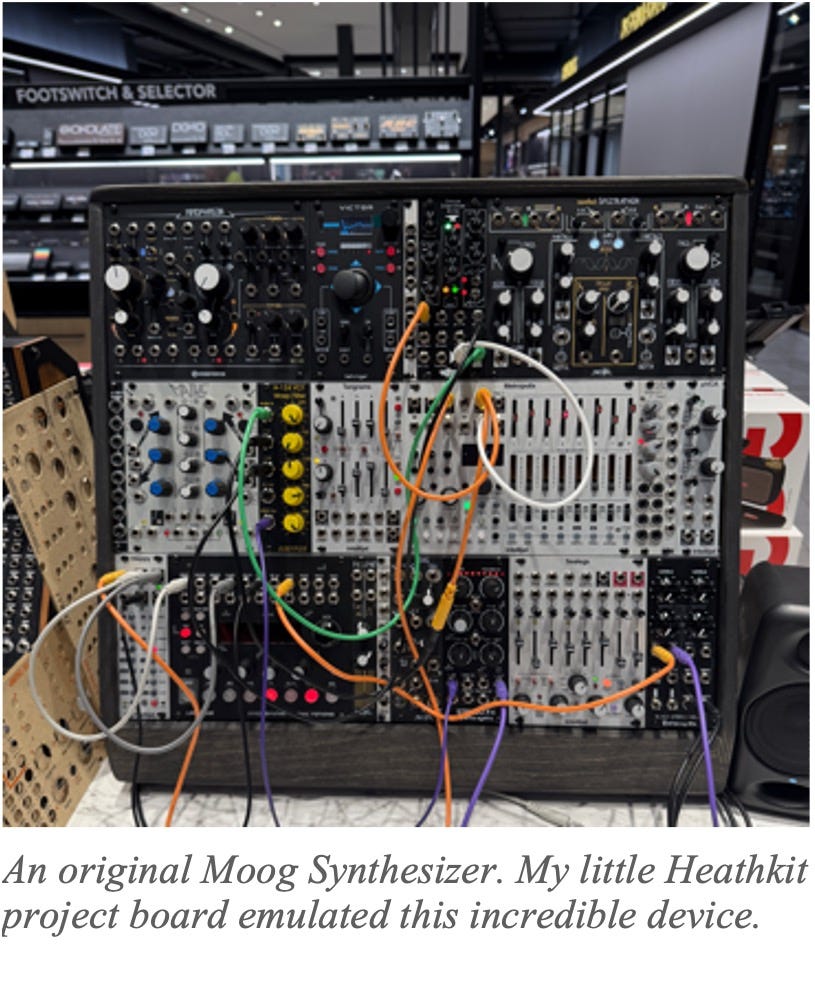

We loved electronics, and geology, and astronomy, and all the many offshoots of biology; we would often gather for electronic component swaps, or rock and mineral trades, or just to build things together or admire each other’s latest acquisitions of exotic reptiles or amphibians. At one point, my parents gave me a Heathkit electronics project board, pre-wired with capacitors and resistors and transistors and coils, each connected to little stainless-steel springs that allowed me to run jumpers between the components to wire the projects outlined in the manual. I will never forget the day I learned that by swapping between different components and by wiring the output to a variable resistor, I could make it play wildly oscillating sounds that would be great as the background music for a science fiction film. I had invented a version of the Moog Synthesizer, before anyone knew what that was.

I learned two of life’s important lessons from Bill Meadows: the immensity of the universe, and the immensity of personal grief. The first, my 13-year-old shoulders were prepared to carry; the second, not so much. One Christmas morning after all the gifts had been opened, I called Bill to see if he wanted to get together, probably to compare Christmas bounty. He couldn’t, he told me; his Mom had just died. Maybe tomorrow, he said, with infinite grace. I didn’t know how to process that level of profound loss, but he did, and the grace with which he carried the pain is something I still think about today.

As I said, we were the Big Bang Theory gang before there was a Big Bang Theory, and Bill was our Sheldon Cooper—not in the awkward, geeky way of the show’s lovable main character, but in the brilliant, quirky, knowledge-is-everything way of smart, driven, passionate people. He went on to become a gifted composer and musician, a semiconductor designer, and of course, a top-notch quasi-professional astronomer. We’re still very much in touch; recently, he guided us when Sabine bought me my own telescope. Yes, it’s true. She’s awesome.

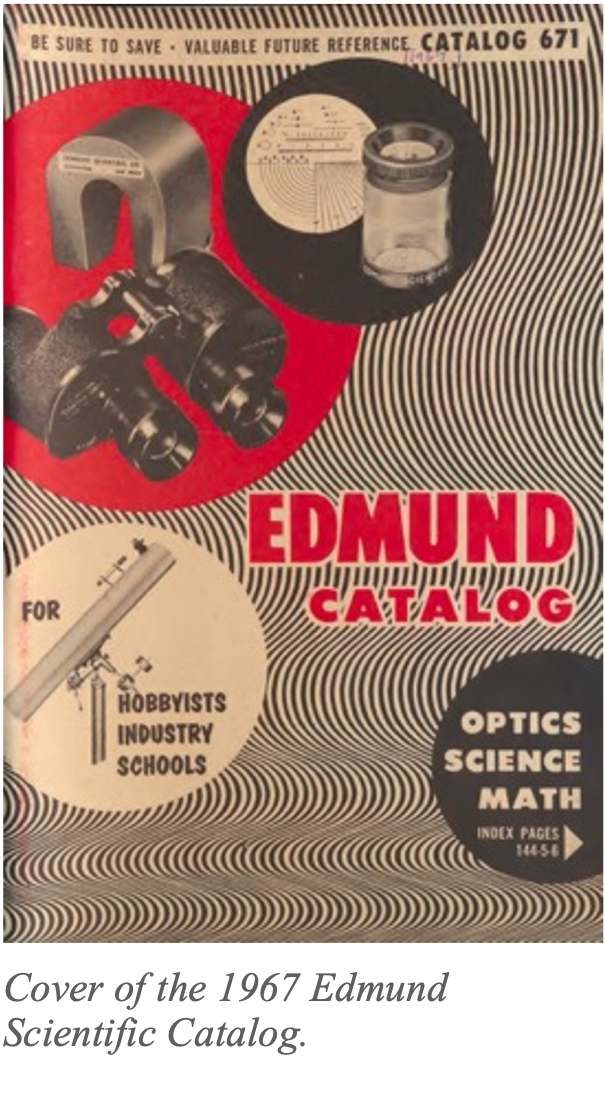

Like teenage boys everywhere, a glimpse at a copy of Playboy was something to be whispered about for weeks, but the publication that really got our motors humming was the annual catalog from Edmund Scientific Company. Sad, I know, but have you ever SEEN a catalog from Edmund Scientific?

Bill, like the Edmund catalog, was an endless source of knowledge and information. I can still remember things I learned from him. Like, how many sides an icosahedron has (the answer is 20). What an ellipse is, and how to make one (slice the top off a cone at an angle). How to work a Foucault Tester. What ‘New General Catalog’ and ‘Messier Numbers’ mean (unique designators for star clusters, galaxies, and nebulae). Why it was appropriate to drool on a Questar Telescope if I ever found myself in the same room with one.

I even remember the night my Mom was driving us to a long-forgotten presentation at the junior high school. As a car went by us at high speed, the sound rose and fell with its passing. In unison, Bill and I said, “Doppler Effect,” then we laughed. But I was a bit awestruck. I was one with the dude.

Somewhere around 1967, Bill decided that something was missing in his backyard. Not a tomato garden, or a jungle gym, or a trampoline; not a picnic table, or a barbecue grill, or a weight set. No, this 13-year-old decided that what was missing, what would really round the place out, was an observatory. His Dad agreed, and they built one. We all helped a little bit here and there, but this thing was Bill’s baby. It looked like half of a shoebox with a giant tuna can sitting on top, and the whole thing sat at roofline level on top of four pieces of drilling pipe punched into bedrock. Coming up through a hole in the center of the floor was a fifth piece of pipe which ultimately became the telescope mount, isolated from the observatory structure so that our walking about didn’t vibrate the telescope when it was focused on whatever it was focused on. The top and side of the tuna can had a two-foot-wide slit that could be opened for viewing. Many were the nights that we had sleepovers at Bill’s house, curled up and freezing in the observatory as we focused the telescope on distant celestial objects, things Bill could casually name and describe from memory, having seen them many, many times with whatever telescope he used before he built the big one.

The big one: Edmund Scientific sold it all. But buy a ready-made telescope? Piffle, said Bill, or whatever the 1967 equivalent of piffle was in west Texas. Instead, he created a shopping list:

• First, a large quartz mirror blank, which was 12 inches or so in diameter;

• Assorted grits to hand-grind a parabolic surface into the blank;

• A Foucault tester to ensure the mirror curvature was correct;

• The tube for the telescope body;

• An adjustable mirror mount;

• The eyepiece ocular;

• Assorted eyepieces;

• An equatorial mount to attach the finished telescope to the center drilling pipe;

• And of course, various accessories: counterweights, a spotting scope, and assorted mounting hardware.

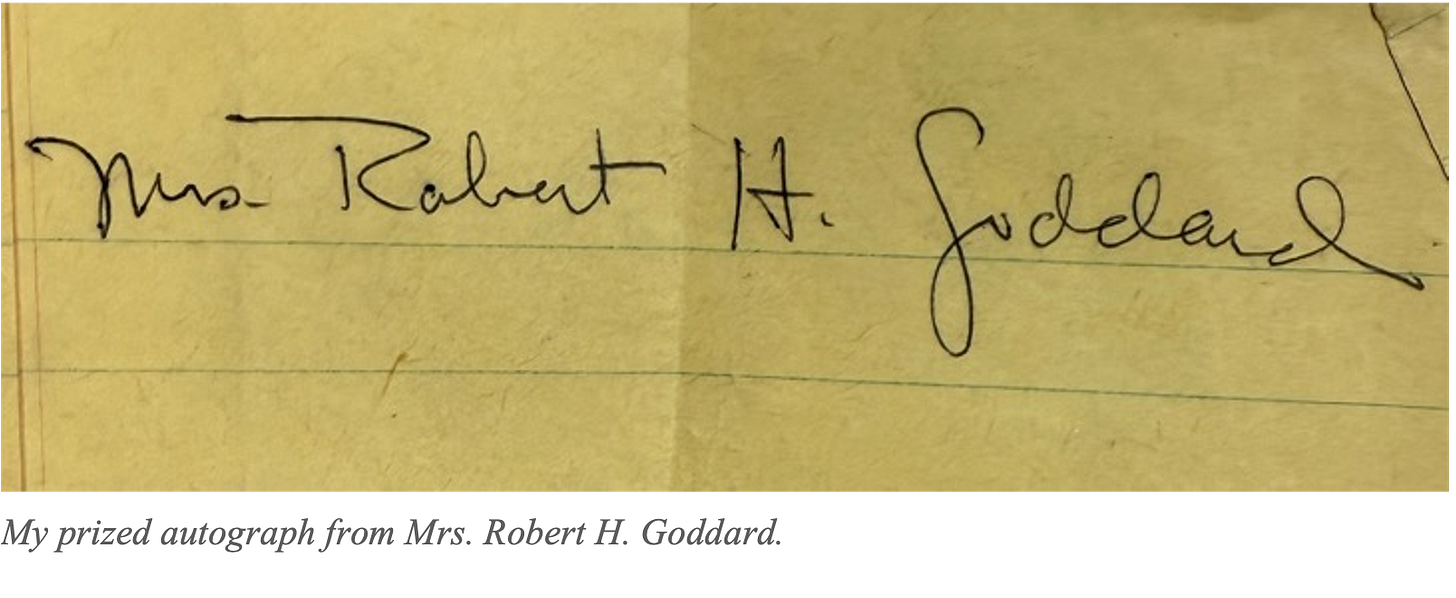

We all claimed some of the credit for building that telescope because all of us spent time hand-grinding the blank under Bill’s watchful eyes. But make no mistake: it was Bill who built that thing. He ground and ground and ground, week after week after week, starting with a coarse abrasive grit and grinding pommel, then onto a finer grit, and then finer still, until he was working with red polishing rouge at the end. I remember his pink-stained fingers at school. School: it was so fitting that we attended the brand-new Robert H. Goddard Junior High School in Midland, Texas, complete with rockets mounted on stands out front. Goddard, who invented the modern liquid-fuel rocket, was long dead, but his wife came to visit the school not long after it opened. I still have her autograph.

It’s interesting to me that Goddard designed and launched his rockets near Roswell, New Mexico, where my maternal grandparents lived, and where … well, you know.

Once Bill was done with the grinding and polishing, he shipped the mirror blank back to Edmund, and they put the mirrored surface on it and shipped it back, ready to be mounted in the telescope.

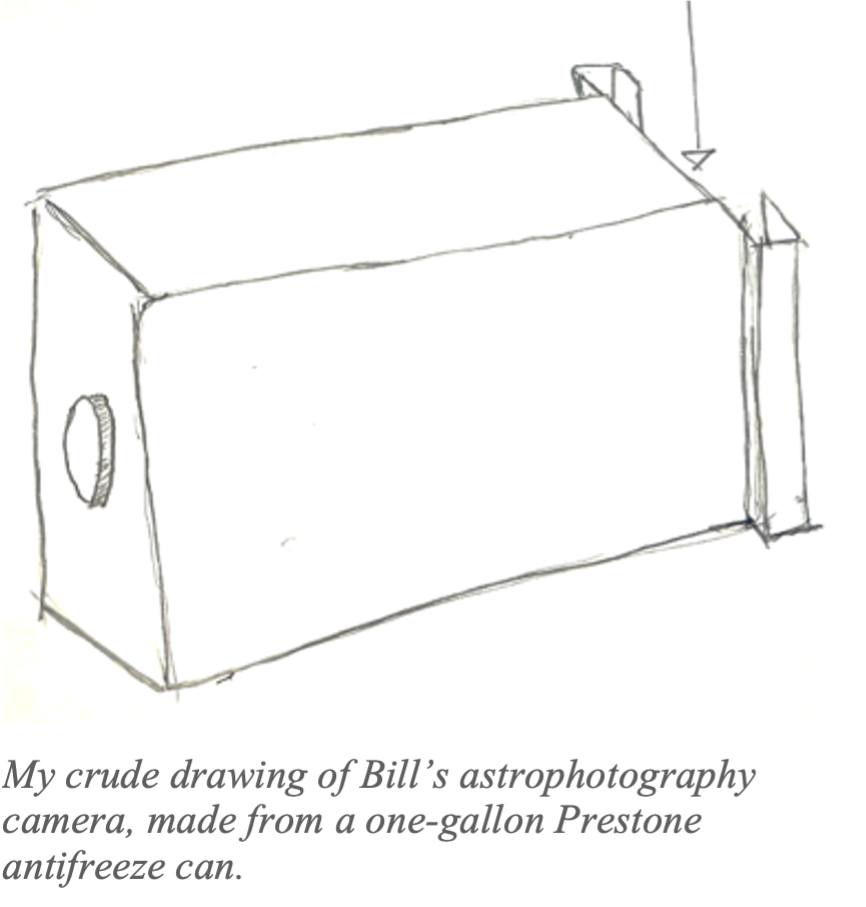

One of Bill’s goals was to do astrophotography. Keep in mind that this was 1968, and photography wasn’t what it is today. There was no such thing as a digital camera (mainly because there was no such thing yet, really, as digital anything), and there was no way to mount a standard camera on a telescope. So, Bill improvised in an extraordinary way. He took a one-gallon metal Prestone antifreeze can and cut the top off. He then flocked the inside of the can with a very dark, matte black paint to eliminate reflections. In the middle of the bottom of the can he cut a two-inch hole, and there he mounted a T-connector, which would allow him to attach it to the eyepiece holder of the telescope.

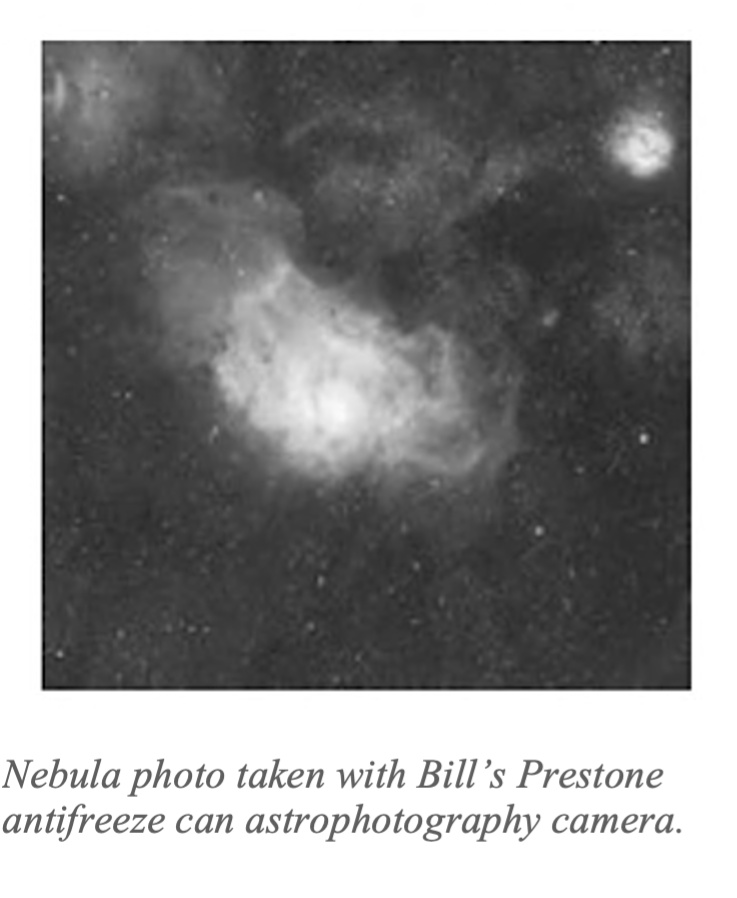

Now came the genius part. Using tin snips, he cut and bent the open top of the can so that it had two flanges, one on each side, which would neatly and securely hold a sheet film carrier plate. The plate was about five by eight inches, and once it was in the “Prestone camera” and the environment was dark, he could slide out the cover that protected the sheet film from light, and the image of whatever was in the viewfinder would be splashed on the film. Minutes later, Bill would slide the cover back in, and after sending it off to be developed, he’d have a time-lapse photograph. In fact, I still have a photograph he gave me of the Orion Nebula somewhere in my files, along with one of a long-forgotten star cluster.

It was cold in that observatory; a heater was out of the question, because the rippling heat waves escaping through the observatory’s viewing slit would ruin the image area—another thing I learned from Bill. So, cold it was.

We weren’t supposed to have the kinds of conversations we did at that age, but they made sense, which was why Bill’s explanation to all of us about what we were taking turns looking at was—well, normal. “A true binary star system,” he explained, “is two stars that are gravitationally bound together and therefore orbit each other.” I can still remember, all these years later, that we were looking atSirius, sometimes known as the Dog Star, the single brightest star in the night sky, at least in the northern hemisphere. It’s part of the constellation Canis Major. “Sirius A is a bright star and Sirius B is a bit dimmer,” Bill told us, “but the ‘scope can resolve them.” Today, every time I look up and see Sirius, I think of Bill.

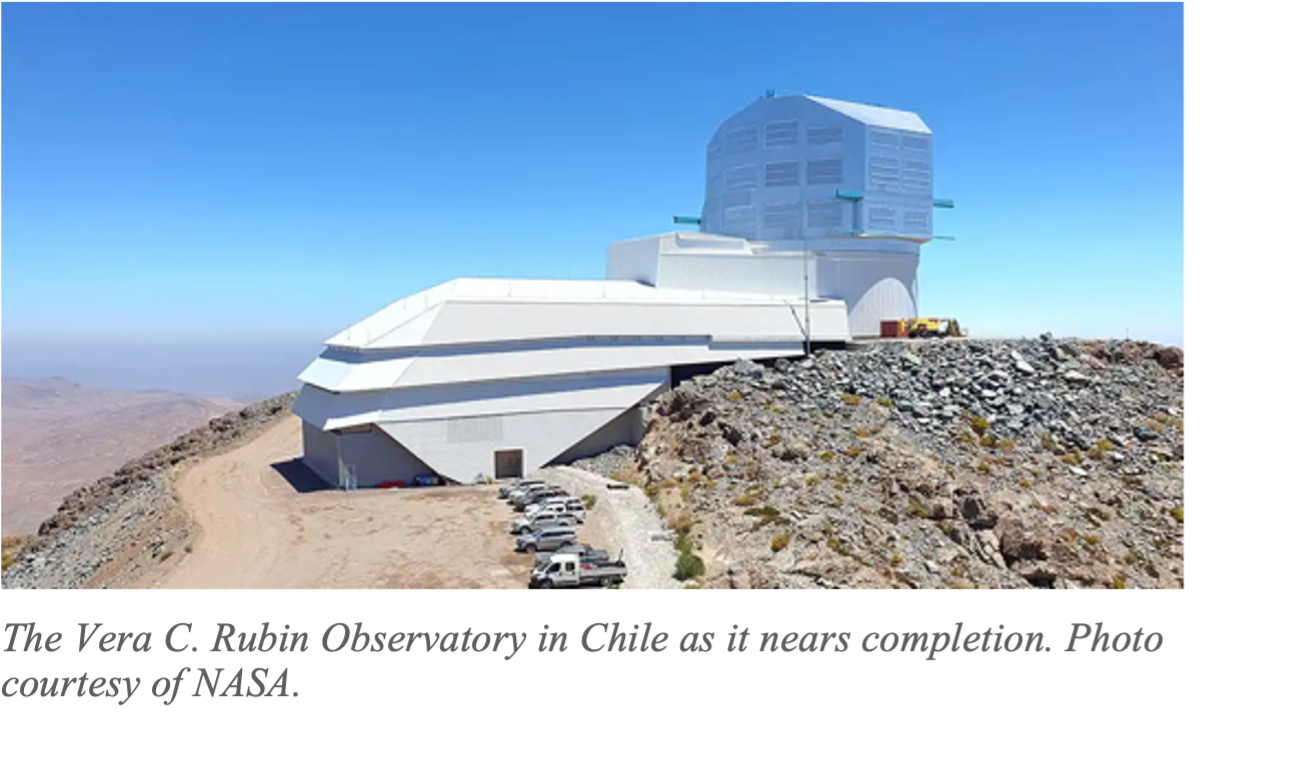

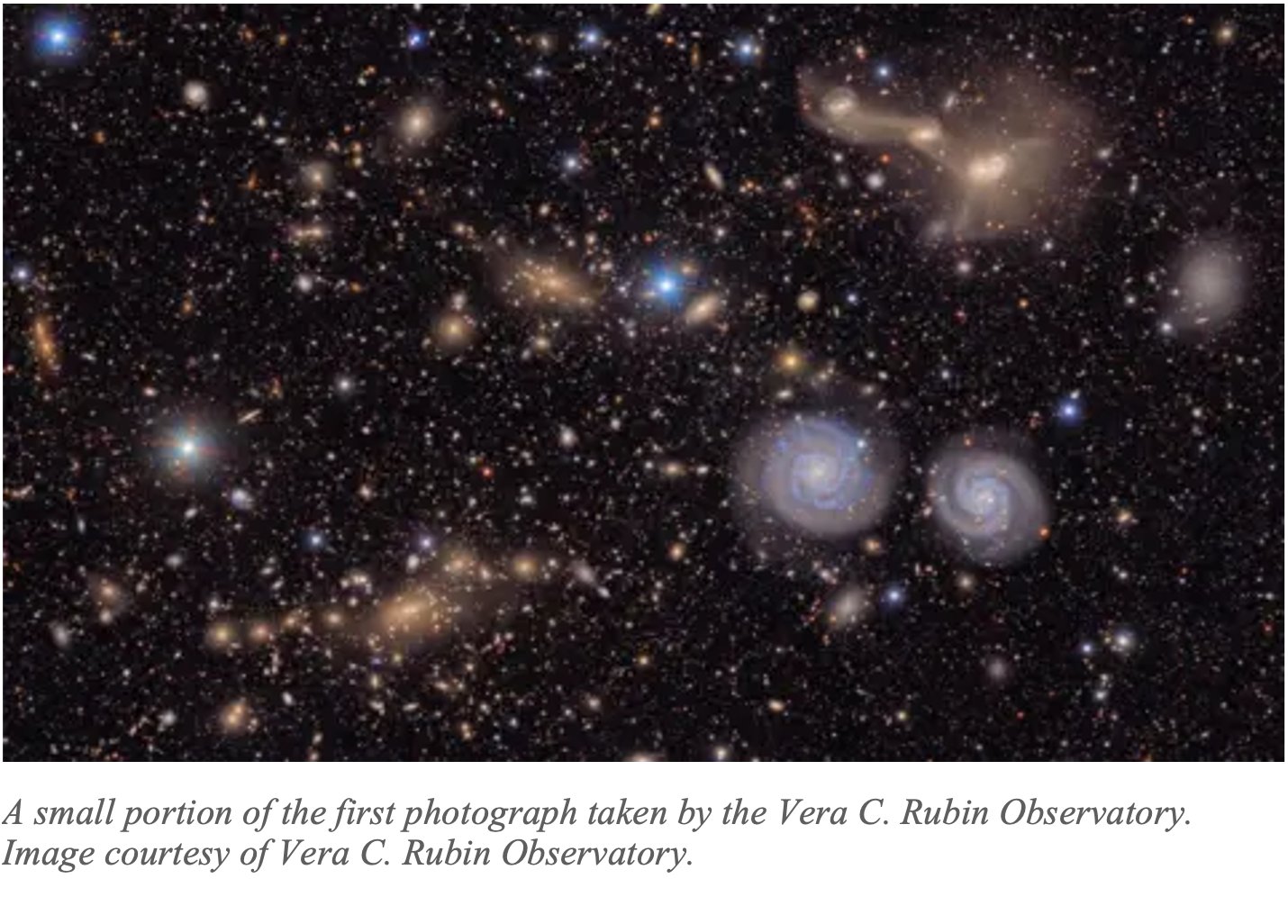

This essay is about the relationship between curiosity and awe and wonder, so let me ask you a question. First, when was the last time you can remember being genuinely curious about something, something new to you, something that made you curious enough to do a little reading or research about whatever it was—and to then be awed by it? Just yesterday, June 23rd, 2025, the very first images from the brand-new Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile were shared with the public. Within two days of its first scan of the night sky, the Rubin telescope discovered more than 2,000 new asteroids, and astronomers predict that over the next ten years it will capture images of 89,000 new near-Earth asteroids, 3.7 million new main-belt asteroids, 1,200 new objects between Jupiter and Neptune, and 32,000 new objects beyond Neptune. Doesn’t that make you just a little bit curious about what ELSE might be lurking out there? Doesn’t it make you feel a certain amount of awe and wonder, if for no other reason than the fact that humans have developed the scientific wherewithal to build this amazing machine?

Part 2

One of the first things I realized when I got my new telescope a few months ago and began to thaw out long-forgotten astronomy knowledge, was that a telescope is a Time Machine. Here’s why.

The night sky is filled with countless observable objects, other than the moon and stars. For example, on a dark clear night, chances are very good that if you lie down on a lawn chair in your backyard and turn off the porch light, within 15 minutes you’ll see at least one Starlink satellite sweep past. If you time it right and look just after sunset, you’re likely to see the International Space Station pass overhead, the light from the setting sun reflecting off its solar and cooling panels. There’s even an app for your phone to track its location.

Then there are the natural celestial bodies. Depending on the time of year, it’s easy to spot other planets in our solar system with the naked eye, especially Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. They, like the Earth, orbit our sun, which is, of course, a star. It is one star in the galaxy known as the Milky Way, a collection of stars, planets, great clouds of gas, and dark matter, all bound together by gravity. The Milky Way is made up of somewhere between 100 and 400 billion stars. And remember, that’s a single galaxy.

In the observable universe, meaning the parts of the universe that we can see from Earth with all our imaging technologies, there are between 200 billion and two trillion observable galaxies, each containing billions of stars.

So just to recap: the Earth orbits the Sun, which is one of 100 to 400 billion stars in the Milky Way Galaxy. But the Milky Way Galaxy is one of somewhere between 200 billion and two trillion galaxies in the observable universe. And the observable universe? According to reliable, informed sources—NASA, the Center for Astrophysics at Harvard, and the Smithsonian—we can observe five percent of it. 95 percent of the universe remains unknown and unseen.

Starting to feel it yet? It’s called awe and wonder, and that itch you’re feeling? That’s curiosity.

Part 3

If you lookto the north on any given spring evening, you’ll easily spot the Big Dipper, a recognizable part of the constellation, Ursa Major—the great bear. Here’s an interesting fact for you: the Big Dipper isn’t a constellation. It’s anasterism, which is a pattern of stars in the sky that people have come to know. The Big Dipper is an asterism that’s part of the more complicated constellation known as Ursa Major.

Take a look at a photo or drawing of the Big Dipper. It consists of four stars that form the “bowl” of the dipper, and three stars that make up the dipper’s curving “handle.”

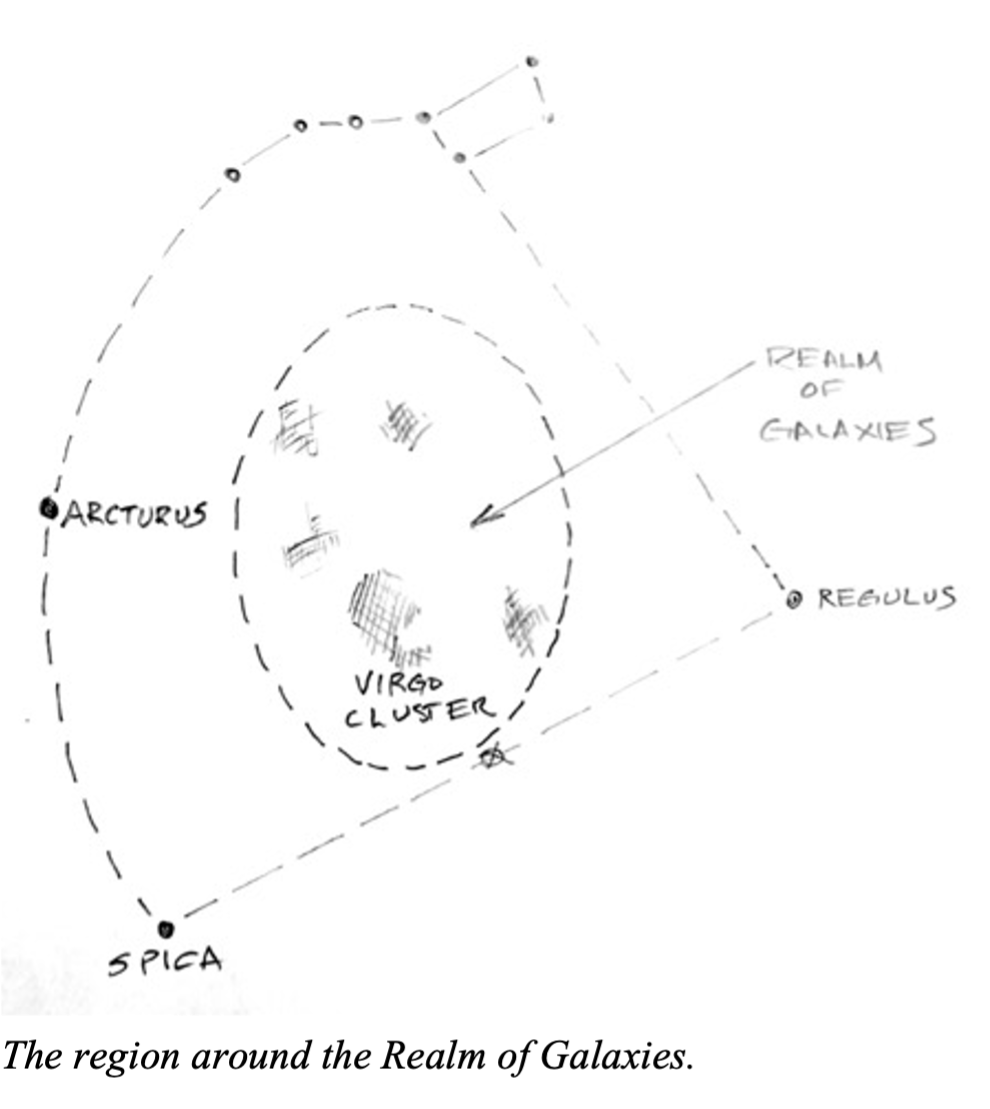

The handle forms the beginning of a celestial arc, and if you extrapolate it you can “follow the arc to Arcturus,” a very bright star in the constellation Boötes. From Arcturus you can “speed on to Spica,” a fairly bright star in the constellation Virgo. You can do all of this with your naked eye.

Now: go back to the bowl of the Big Dipper. Draw an imaginary line from Megrez, the star where the handle attaches to the bowl, through Phecda, the star just below it that forms a corner of the bowl, and keep going to Regulus, the brightest star in the constellation Leo.

If you now draw a line between Spica and Regulus and look slightly above the midpoint of that line, you are staring at a region of space called the Realm of Galaxies.

I love that name; it sounds like a place that Han Solo would tell Chewy to navigate the Millennium Falcon to. Nowhere else in the visible sky is the concentration of galaxies as high as it is here. Within this space, for example, is the unimaginably huge Virgo Cluster of galaxies. How huge? Well, the local cluster, to which our spiral-shaped Milky Way and Andromeda Galaxies belong, contains a mere 40 galaxies. The Virgo Cluster has more than a thousand, but those thousand are packed into an area no bigger than that occupied by our own local cluster with its 40 galaxies. And remember, each of those galaxies is made up of billions of stars.

Galaxies are active, often destructive behemoths. When a small spiral galaxy like our own Milky Way gets too close to a larger one, things happen. The Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, which are members of our local cluster, used to be much closer to the Milky Way, but the Milky Way’s gravity stripped away many of those galaxies’ outer stars, creating distance between them and radically changing their galactic shapes. But the Milky Way hasn’t finished its current rampage: it’s now in the process of dismantling the Sagittarius Galaxy.

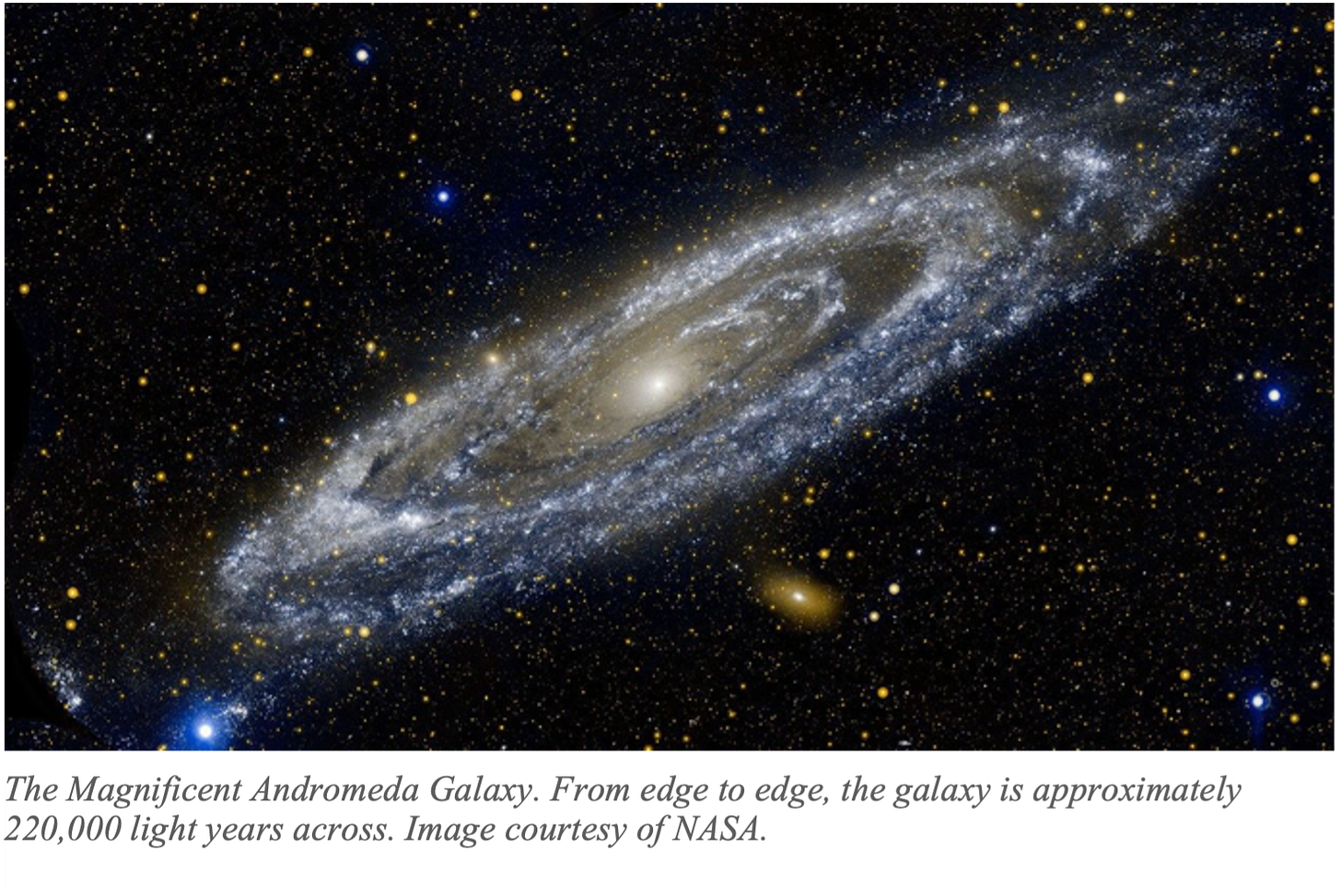

These things are also big—far bigger than we’re capable of imagining, as are the distances between them, which is why I said earlier that a telescope is a fully functional Time Machine. Andromeda, for example, is 220,000 light years across. You need a wide-angle eyepiece to look at it through a telescope. For context, consider this. The speed of light is a known constant—it never changes. Light travels at 186,000 miles per second, or just over 671 million miles per hour. Think orbiting Earth’s equator 7-1/2 times every second. That means that in one year, light travels 5.88 trillion miles. We call that a light year. It’s not a measure of time; it’s a measure of distance. To fly from one end of Andromeda to the other would take 220,000 years, at 186,000 miles per second. Pack a lunch.

When you look up at Andromeda, which is our closest galactic neighbor, you’re looking at an object that is two-and-a-half million light years away. What that means is that the light striking your eye has traveled 14 quintillion, 700 quadrillion miles to get to you. That’s ‘147’ followed by 17 zeroes. More importantly, it means that that light left Andromeda on its way to your eye two-and-a-half million years ago. Two-and-a-half million years ago: the Pleistocene epoch was in full swing; Earth’s polar ice caps were forming; mammoths and mastodons roamed North America; the Isthmus of Panama rose out of the sea, connecting two continents; the Paleolithic period began; and Homo habilis, the first protohumans, emerged.

All that was happening when that light that just splashed onto your retina left its place of birth. And that’s the closest galaxy to us.

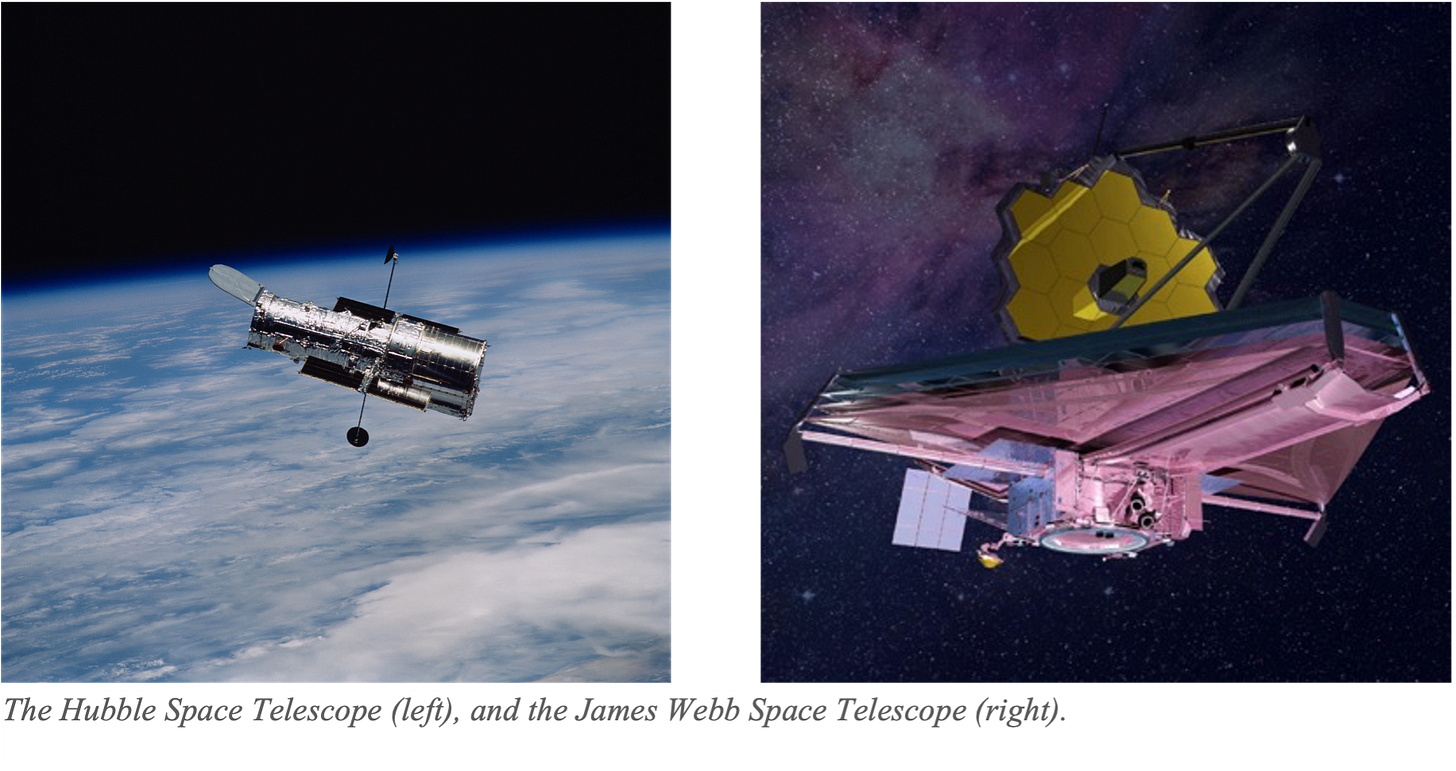

So, I’m compelled to ask: is Andromeda still there? Do we have any way of actually knowing? A lot can happen in two-and-a-half million years. And now, with the breathtakingly complicated telescopes we’re placing in deep space—the original Hubble got us started, and now with the James Webb Space Telescope, we’re capturing infrared light that is 13.6 billion years old. The universe is 13.8 billion years old, which means that we’re getting close to seeing as much light as it’s possible to see from the formative edge of the universe itself—what’s known as the cosmic event horizon. Which, of course, begs the question: what lies beyond the edge?

Part 4

Curiosity, awe, and wonder are amazing things. They feed, nourish, encourage, and drive each other, and in turn, they drive us. I love this science stuff, especially when it hits us with knowledge that is beyond our ability to comprehend. For me, that’s when curiosity, awe and wonder really earn their keep. Because sometimes? Sometimes, they’re the only tools we have.

You had an amazing childhood. No wonder you have such a sense of awe.